ERM Builds Post-Mining Land Use Model with isee systems Expertise

Paul Hesketh

Paul Hesketh

Mining is an essential, but often unpopular, business. It delivers the metals and minerals that fuel

modern technology (e.g., solar panels, any device that needs a battery) and make up everyday items

(e.g., currency, salt, glass, concrete, ceramics). It also creates jobs that build communities. But

the digging and blasting it requires and toxins it emits are hard on the environment. And what will

happens when the mine closes? Will the area around it be safe? Will runoff degrade the health of

local water systems? Where will former employees work?

“Mining is a lifecycle business,” says Paul Hesketh, Global Mine Closure Lead (Europe, Middle East,

Africa), ERM, a multinational advisory firm focused on sustainability. “We use a mining and metal-wide

strategy to support clients from the permit process through closure. Closure is always complicated and

expensive. Every mine is different and varies in size and scale so closure projects cost anywhere from

$100 million to $1 billion.”

When closing a mine in the past, it was deemed enough for a mine to simply make a site safe from personal

injury – fill in holes, remove dangerous equipment—before leaving the site. Post-closure disasters

proved those basic steps were hardly adequate. In 1966, a coal waste landslide killed 144 people in Aberfan,

England. In 2019, a tailings (mine waste) dam, built by a Brazilian mine that closed in 2018, failed and

caused a mudslide that covered nearby homes, farms, inns, and roads, as well as mine buildings. Two hundred

and seventy people died.

Those disasters and many others have led to higher safety standards for mine closure. They have also

shined a light on the damage that mining leaves behind and increased emphasis on environmental and economic

sustainability through well-managed post-mining land use.

“Mines now include ‘restore the environment’ measures in closure plans,” says Hesketh. “For example,

they address the problem of mine runoff that carries acids and toxic particles like iron into streams

and rivers. They also include strategies for repairing wildlife habitats.”

Improperly closed mines also negatively impact the communities outside of, but related to, the actual

site. “Mining closures can have a big impact on people,” says Hesketh. “A town’s workforce might be

dependent on a mine. There might not be another mining or commercial operation to support workers

which hurts the local economy. Even people who don’t work in mining—shop keepers, teachers,

doctors are impacted when their clients lose their jobs.”

National and local governments are beginning to require post-mining land use plans that restore or add

value. “Especially in places like South Africa where large populations live near mining sites, licenses

to operate now require post-mining commitment,” says Hesketh.

In 2023, a multinational mining company sent out a request for proposal for a mining ecosystem model.

While they were concerned about one particular site, they wanted a model that could be used anywhere

in the world. “They knew what they wanted, they could picture it, but they didn’t know how to build

it,” says Hesketh.

The model was to work within a broader framework of post land use mine (PMLU) planning, highlighting

specific projects that would drive value from the site for 30 years after the mine closes. The

framework includes both prework, before running the model, to determine possible projects for the

site and post work, after running the model, to determine the viability and implementation of the

best basket of projects according to the model. The outcome would be the PMLU plan.

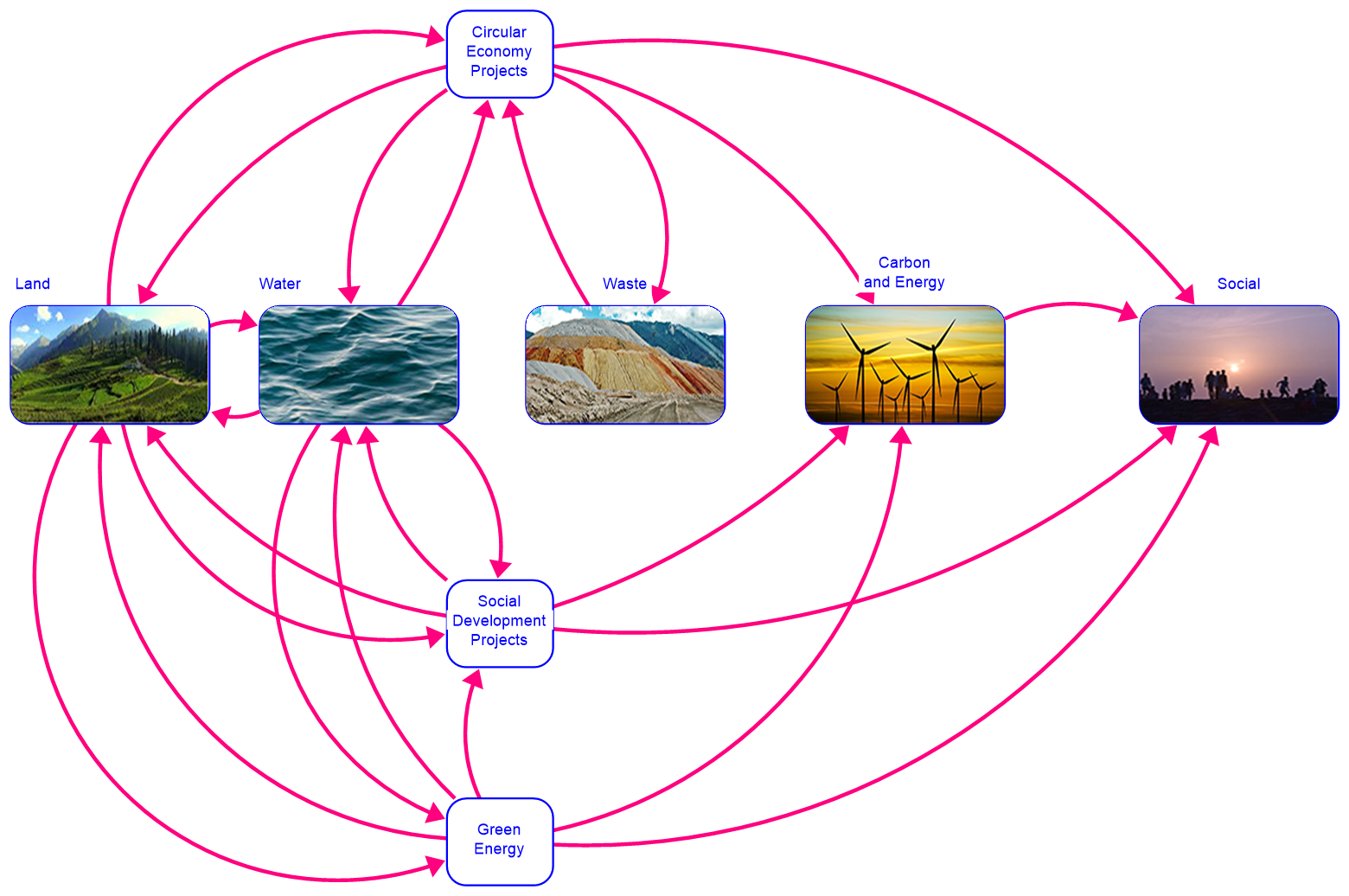

The core structure of the model had to be based on the mine’s five value drivers: Land, Water, Waste,

Carbon and Energy, and Social. Each of these would be affected by a large suite of potential projects that

would drive a different amount of value, whether that is jobs (social), clean water, fertilizer, etc.,

depending on the specific project and its scale.

Hesketh and his associates at ERM began looking at system dynamics software that could support the project.

“We found several packages and quickly saw that isee systems offered the most commercial, end-user friendly

software,” says Hesketh. “We also noticed the isee systems consultancy opportunity and liked the idea of

including real system dynamics expertise in proposal development and model building.”

Karim Chichakly, Co-President of isee systems, joined the ERM team, which includes staff in South Africa,

the United Kingdom, and Canada. After winning the mining ecosystem model contract, the team began

working with the client to develop a model that projects mine closure outputs and measures the value

developed through various closure measures. “The model assesses the closure plan value in terms of jobs,

agricultural land use, water diversion and re-use, energy, carbon abatement, and a host of other outcomes,”

says Hesketh. The model allows the user to enter what is most important to them, in terms of the five value

streams, and evaluates the performance of each basket against that criteria.

High-level overview of the model

High-level overview of the model

“We began the project in July 2023. First, we developed a clear understanding of what isee can deliver.

Then we learned about the world in which the model lives, the types of mining projects the client

oversees. Karim detailed the kinds of information he needed to build the model and the data needed

to run simulations. We worked with the client to collect that information and data. As we use the model,

we see things that need to be added or refined.”

The team learned an important insight even before the model was finished. “Clients don’t have all the

real-world information needed to build or run the model,” says Hesketh. “They have business plans that

describe their operation, but only some of the data needed to look at water use, runoff and waste, energy,

and other variables. We had to generate made-up, ideal—but realistic—situations and data when actual

information wasn’t available.”

As they tested the model, the team and their client realized that water was almost always the main system constraint.

“Water is an input to just about every post-mining activity, especially agriculture,” says Hesketh. “Growing food

or raising animals requires access to clean water, which means that mine closure plans have to include treating

or diverting water to keep toxins out of irrigation systems. Value is added through the addition of low-level

water management jobs and food processing businesses.”

The ERM team categorized the large number of projects into three main areas: Circular Economy, Social Development,

and Green Energy. The projects were then generalized to 16 archetypes, which are flexible project templates

that include, for example, Waste to Land (fertilizer), Agriculture: Crops, Residential, Solar Farm, and

Nature-based Solutions (replanting forests). “The archetypes can be used in any number or combination

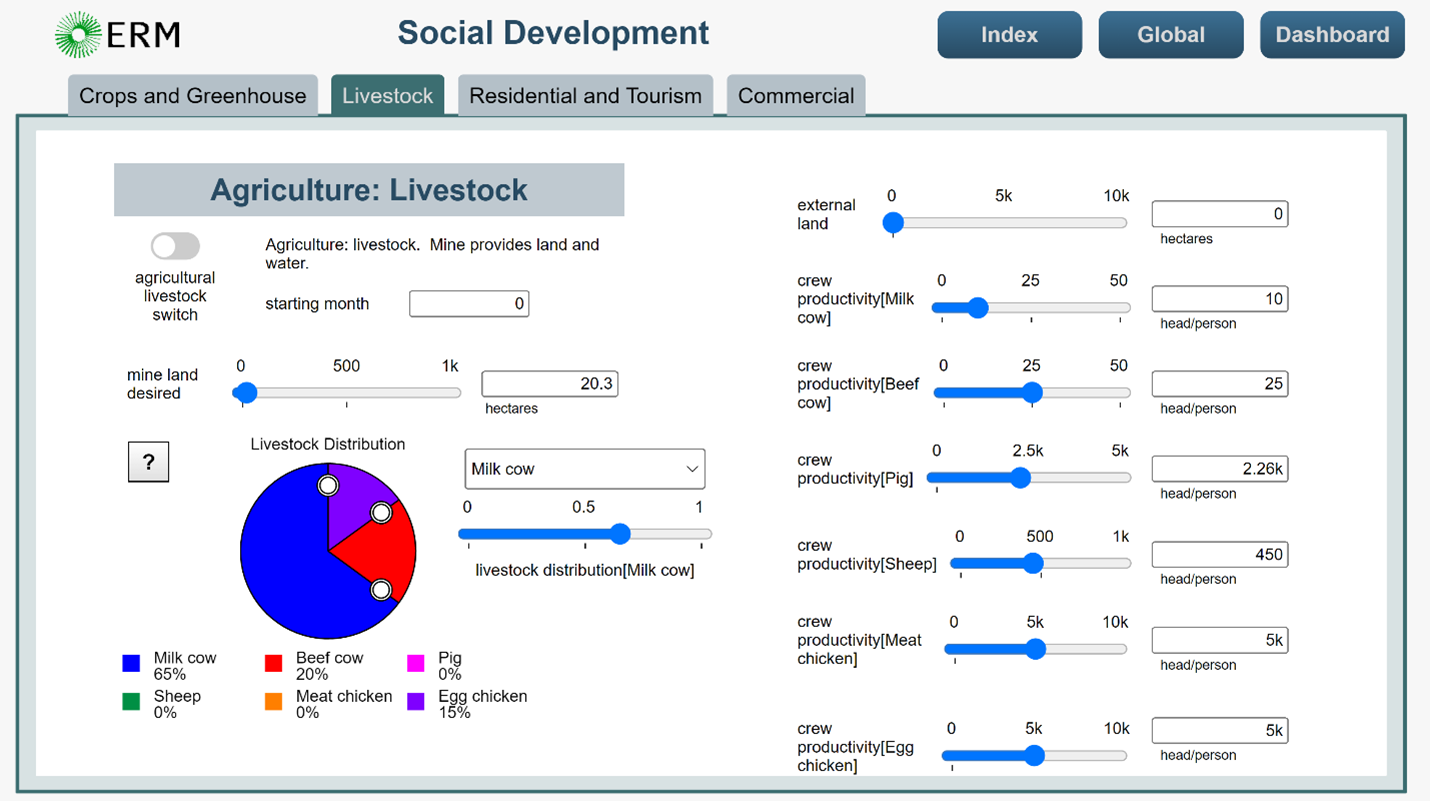

to model millions of situations,” says Hesketh. “For example, if we’re looking at post-mining

agriculture, we can model beef, poultry, or pig farming operations and consider the acreage

requirements of each type of animal and every type of farm—free range to factory.”

Livestock (agriculture) archetype data entry panel

Livestock (agriculture) archetype data entry panel

The model has a friendly user interface that lets the user set the specific parameter values for their

projects and turn archetypes on and off. Simulating the model assesses the value of mine closure

outcomes, but also warns the user of constraints that are restricting access to greater value.

After a longer period of model testing, use, and client feedback, the ERM team will make refinements and

add capabilities. “We already know that we need to implement a new archetype that assesses biodiversity,

which is a big part of environmental restoration,” says Hesketh.

Modeling mine closure value is ERM’s first foray into system dynamics. “It’s been a very positive

experience,” says Hesketh. “The model is being presented at conferences in Norway and Perth, Australia

this year. At first, we were a bit skeptical that we could meet the client’s needs, but bringing isee

systems and Karim onto the team made the difference. We’ve worked really well together.”