SKIP Explores Early Childhood Education Challenges and Interventions Using Stella®

Saras Chung

Saras Chung

Most taxpayers would vote an enthusiastic “Yes!” for a program that promises to yield a 13% return on investment.

That’s what social scientists have estimated high-quality early childhood education programs return to their

communities. By preparing young children for success in school, early childhood education positions them for

higher levels of education, steadier employment, better housing, and better health. Why, then, don’t all young

children have access to early childhood education programs?

Concerned citizens in St. Louis, Missouri asked this very question in 2017. Data showed that only 50% of St.

Louis’ eligible 3- and 4 year-olds were enrolled in early childhood education programs of questionable

quality, and citizens wanted to make sure that the city was providing equal access to all children. They

brought their concern to Saras Chung, MSW, PhD, who was working as a computational social scientist at Washington

University in St. Louis’ Social System Design Lab. The pro bono consulting she began led to a project proposal and,

eventually, the establishment of SKIP, a strategy organization that co-designs systems change initiatives with

communities.

“We realized that understanding and improving accessibility to programs wasn’t a project, it was a long-term

process with many stakeholders,” says Chung. “We created SKIP to contribute to that process by serving as a

design resource for the community and a way to make it easier for stakeholder groups to apply system dynamics.”

Chung and her team began by reaching out directly to people in the community. “We wanted to hear from families

who weren’t accessing early childhood education programs, people who were disconnected from that system,” says

Chung. Radical listening techniques that enable interviewers to strike up conversations with strangers were used

to gather insights in the most impacted neighborhoods. The information collected led to the team’s first ‘aha’

moment.

“We started our inquiry wondering about barriers to enrollment in early childhood education programs,” says Chung.

“Did parents, some of them eligible for government subsidies or free tuition, not know about benefits or maybe

not care?”

In fact, parents cared very much about their kids' early childhood experiences. The radical listening effort uncovered

that parents perceived program quality and safety to be questionable. “Parents had heard stories about kids just

watching videos all day or being harshly punished,” says Chung. “Some of them had experienced abuse in their own

early childhood program experiences. They reported being scared for their kids and sure that Grandma’s house would

be safer.”

That insight on perceptions led to a fuller investigation of the early childhood education system. The SKIP team

identified four interdependent feedback loops that drive early childhood education program accessibility and

quality in St. Louis:

-

Accessibility for parents: The cost of early childhood education in St. Louis ranges from 10 to 15% of

household income. Subsidies available to lower income families don’t cover full costs, and the lower

the cost, the lower the quality. Even programs that are affordable and high quality may not meet families’

needs for hours of operation, location, or availability of seats.

-

Perception of Quality: Even when cost isn’t a factor, parents are leery of enrolling their child in a

program that doesn’t have a good reputation. As worries about quality and safety hinder enrollment

from bad word of mouth, programs find it difficult to stay open, which impacts accessibility.

-

Workforce quality and maintenance: The early childhood education workforce in St. Louis has a 30% annual

turnover rate. Low wages and few opportunities for career advancement cause talented teachers to

leave the profession, which impacts availability of seats and lowers actual and perceived quality.

-

Viability of the business model: It is expensive to deliver high quality early childhood education.

Tuition has to cover costs for insurance, facility rent and maintenance, equipment and materials,

food, administration and, of course, staff, where the number of teachers available to students is

government mandated. In St. Louis, average tuition rates cover only 40% of high-quality program costs.

Government subsidies cover only 32%. The inability to cover costs leads to across the board cutting

including staff salaries, which impacts turnover, availability of seats, and real and perceived quality.

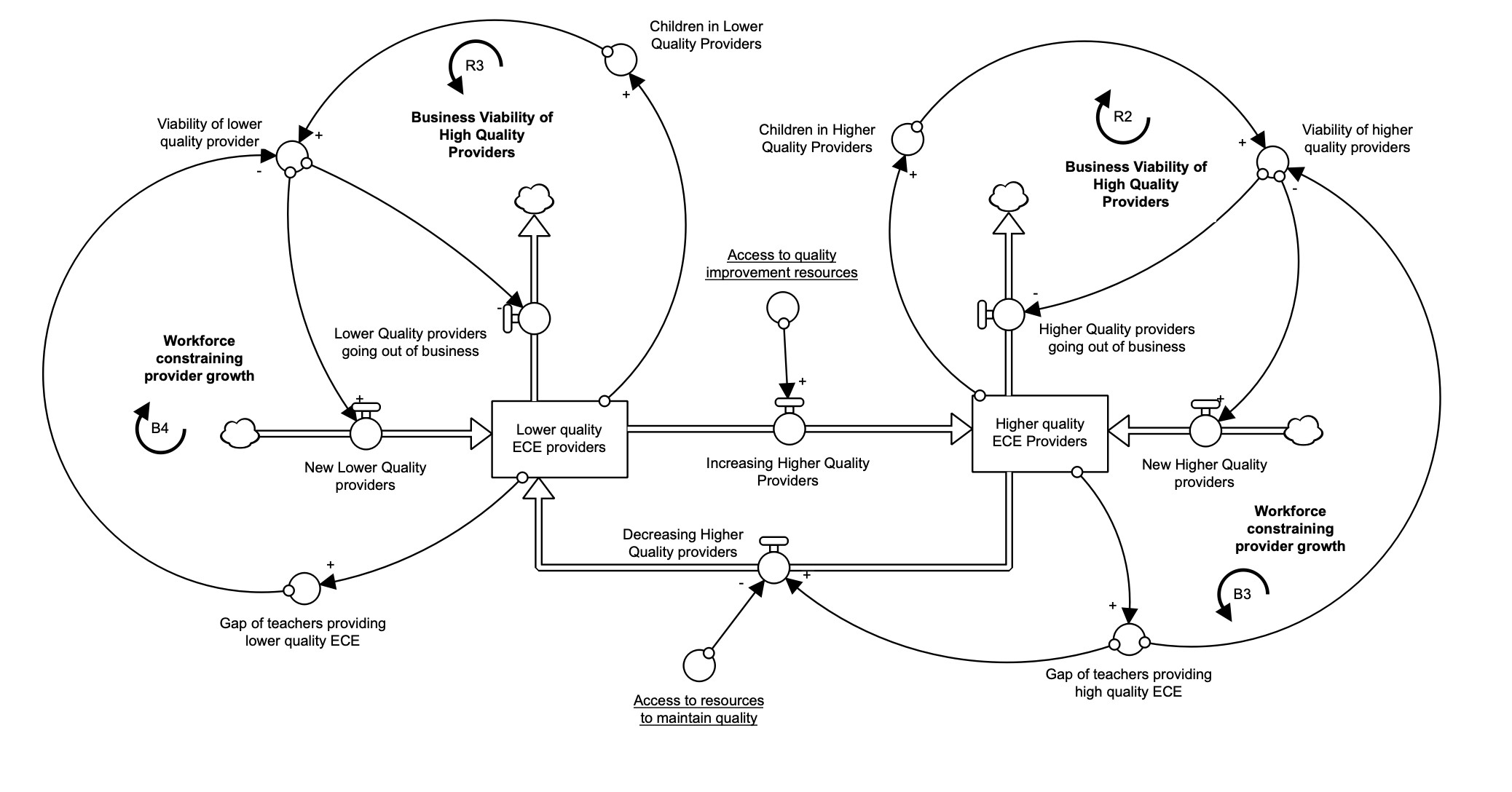

This “Provider Structure” models the dynamics between early childhood

education provider business viability, workforce availability, and quality.

This “Provider Structure” models the dynamics between early childhood

education provider business viability, workforce availability, and quality.

The connection of those feedback loops helped the research team see past a few assumptions. “We initially

thought that the cost of programs seats was tied to availability, that fewer seats than required was

inflating the cost of each seat,” said Chung. “Adding seats should solve that problem, but, using the

model, we found that adding seats actually lowered program quality due to the inability to keep up with

the workforce, which lowered perceptions of quality and use of the system.”

The model revealed the reason for that counterintuitive dynamic. To increase the number of early childhood

education program seats available, St. Louis would have to hire more teachers. “Adding teachers should

improve the system, but turnover is so high that adding teachers adds to an already challenging hiring

situation and requires constant training for new employees,” said Chung. “Having a constant stream of less

experienced teachers lowers quality, which then lowers perceptions of quality and thereby enrollment.”

Reducing turnover by increasing wages is also problematic. “While higher wages increase teacher retention,

they increase costs, which are already too high for most families,” says Chung. “When one of St. Louis’

school districts instituted a pre-Kindergarten program, which is not mandated by the state, the wage and

turnover problems went away. Unfortunately, the pre-K program pulled three- to five-year olds out of existing

programs, leaving the younger children who require more expensive care.”

Obviously, finding good interventions for a complex system that isn’t working is very difficult. SKIP is

working closely with two organizations that will lead the design and testing of interventions using the

model. WEPOWER Tomorrow Builder Fellows works to activate Black and Latinx changemakers to reimagine and

redesign systems that impact their communities, and the First Step to Equity Collaborative operates to

create a region that makes children a top priority.

“For people experienced in system dynamics, model building is an effective way to learn a lot pretty

rapidly,” says Chung. “The important thing is to build models that other people can use to test assumptions

and design improvements. We used Stella Architect to create an interface that our partners who don't have

system dynamics modeling skills can use for their work.”

To transfer insights and ownership of the model, SKIP is planning sessions to develop system insights with

decisionmakers from the community using the Stella interface. “During the training, leaders will engage

with the model to design interventions. Using interface dials, they’ll see, for example, that when teacher

wages are raised, the costs are passed down to centers and inevitably parents, further restricting accessibility

to the system. It’s important for people to test interventions they already had in mind using the model to

see how their assumptions pan out. Often they’re surprised to see that cherished interventions weren’t as

effective as they first thought.”

For the SKIP team, the power of their work lies in this transfer to community partners. “System dynamics is a

way of thinking that can’t live and die with us,” says Chung. “We have to get other people, especially those

with real-world expertise, involved.”

In addition to working with community decision-makers, SKIP’s website shares “voices” from community members

in the form of quotes and videos, and clear descriptions of the four feedback loops. “The site is built for a

relatively small audience: teachers, administrators, parents, policy makers and other stakeholders in the St.

Louis early childhood education system,” says Chung. “We want them to see new perspectives and also say ‘Yes!

This work does reflect the system we know.”

SKIP and its partners still have a long way to go to influence positive change in St. Louis’s early childhood

education programs, but Chung can see a future beyond that work. “What we try in St. Louis might be useful

in other cities and, since the model is comprehensive, we can broaden our work to the K-12 education system

or go deeper into specific issue areas like compensation and charter/public school fragmentation.”

Whichever road SKIP takes, Stella will help them deliver models that can be used by their partners. “Building

models is more intuitive and faster with Stella,” says Chung. “You save time developing complex formulas, and

the software combs through code to find your mistakes. And, by making it easy to create intuitive interfaces,

system dynamics novices can experiment with ideas and ask ‘What if?’ That’s what models are for. All of this

is about learning and making systems change together.”

For more information, visit skipdesigned.com.